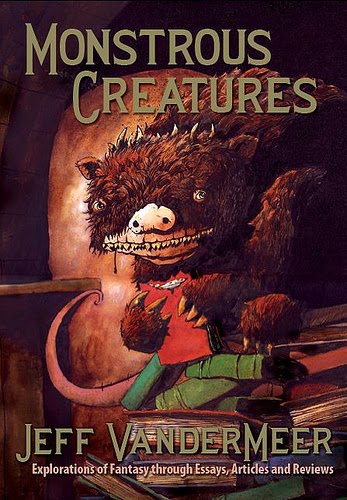

Monstrous Creatures: Explorations of the Fantastical, Surreal, and Weird is the latest non-fiction collection from the award winning author Jeff VanderMeer. It will be released through Guide Dog Books March 11 (this Saturday) at Fogcon in San Francisco, where VanderMeer and his wife and Hugo-Award winning Weird Tales editor Ann VanderMeer are guests of honor. It is here I should pause for full disclosure, which is that I am also VanderMeer’s co-author on The Steampunk Bible, coming out through Abrams Images this May. Co-authorship aside, as an editor and a writer, I have always looked at VanderMeer’s non-fiction as an example to follow in the field of speculative fiction, and here in one convenient volume is his best work since 2005.

As the title hints, the monstrous is the collection’s overall theme, which VanderMeer’s introduction defines as “the intersection of the beautiful with the strange, the dangerous with the sublime. Things that seem to be continuously unknowable no matter how much you discover about them.” VanderMeer extends this definition to the literary life, which to him: “The best fictions always have those qualities. They reveal dark marvels but they withhold some of their secrets as well.” This collection demonstrates VanderMeer’s attempts to uncover some of those secrets through essays, forewords and appreciations, and interviews.

The first thing you notice when opening this volume is how far-reaching his writing goes: from Locus to Bookslut, Realms of Fantasy to The LA Times, io9 to the Barnes and Nobles Review, Clarkesworld to The Believer, it becomes evident that VanderMeer’s interest in writing casts a wide net. Sure everything in this collection pertains to the fantastical, surreal, and weird in genre, but it is with a special focus on genre’s philosophical, literary, and artistic progenitors. Those interested in the state of SF genre politics will find a historical record of those discussions in essays like “Politics in Fantasy,” “The Language of Defeat,” and “The Romantic Underground.” The latter which perhaps best illustrates what I mean by tracing and reuniting genre works with their “literary” progenitors and ancestors. “The Romantic Underground” traces the same literary roots found in today’s new weird, steampunk, and mythpunk (and whatever other -punk that’s hip at the moment). The essay is a pseudo history playing upon the perceived notion that genre needs to fit nicely within an exclusive club, when all along these various movements and counter movements belong to a long and wonderful tradition of Romanticism and Surrealism (and other -isms that were hip way back when). What VanderMeer playfully points out is no matter how you label something—to make it fit in or go against other work and writers— it’s all part of a monstrous collective.

The majority of the book is criticism of other authors and their work, including a large proportion of forewords. As Charles Tan has already written on Bibliophile Stalker, the forewords are insightful critiques of the writers and their work, but as standalone pieces they are something of a reader-tease. However, the inclusion of these severed forewords demonstrate a goal to introduce readers to writers. While some of these forewords and appreciations are of well-known authors like Caitlin R. Kiernan and Jeffery Ford, he also includes looks at more obscure writers like Alfred Kubin, Calvin Batchelor, and Brian McNaughton. VanderMeer’s talent lies in sharing his love with his readers, and the objects of his affection are works from across the seas, or either forgotten or on the cusp of obscurity. Through these essays, various torches are kept lit, attracting writers newer and younger generations of readers.

But for me, the strength of this collection did not lie in these discussions, or in the appreciation of specific writers, but in the more creative non-fiction pieces like “Prague: City of Fantasy,” “The Third Bear,” and his naturalist meditation “Two Essays on Hiking.”

Documenting observations made while visiting the hometown of Kafka and the Golem, “Prague: City of Fantasy” follows VanderMeer through the city and its fantastical literature and art, which seems more like realistic portrature of the city rather than artistic exageration of stragneness. “It was the streets around the Gamba Galley [owned by Jan Svankmajer] that made us realize that some of the more fantastical paintings of Hawk Alfredsone were based on reality. On the streets around the gallery, you will find houses with inward curving walls, delicate slanted ceilings, and tiny doors that look like they came from fairyland.” The piece doesn’t only explore Prague through its culture, but how it was affected by history, as the following describes the residual presence of Communism:

…with the fall of communism Prague was left with a few ugly reminders…like the local television station. Looking a little like a steel cactus, this grim structure fulfilled all of the unimaginative requirements of the Soviet era. But, rather than tear it down, the Czechs commissioned a sculptor to create large “space babies,” which were then attached to the sides of the building. This solution is fun but also offers a mocking comment on the prior regime.

“The Third Bear,” originally published in Brothers & Beasts: An Anthology of Men on Fairy Tales (2007) bridges the gap between fiction and non-fiction by deconstructing the idea and role of the animal (male) predator, but also provides background to VanderMeer’s short story of the same name. The essay begins as a story, but then VanderMeer interjects his voice, his opinion into it: “But I didn’t like the traditional version very much when I read it. I mean, I loved the description of bear and the dynamic between Bear and Masha, but the picnic basket didn’t make any sense. How dumb does Bear have to be to not know that Masha is in the basket?” Throughout the rest of the essay, he reworks and retells the story, all while breaking and setting the fractures found in fairy tales.

There are ways to write academically without being exclusionary or tedious, ways to invite people into the conversation, and “The Third Bear” is the epitome of how to do that. Non-fiction is often thought of as dry, and if it isn’t dry, its creative side tends to be wet with emo tears. But in these essays, VanderMeer is present—he’s giving you an informative tour of the subject—but he is never invasive or presumptuous. Even when he is writing autobiography, which there are several pieces in the last section “Personal Monsters,” he still writes it in an approachable manner.

One autobiographical piece, “Two Essays on Hiking,” seems to stick out from the whole collection. First it is a reworked article from two posts, the first from his older Vanderworld blog in 2005, the other from the popular Ecstatic Days in 2009. The essays relay his experiences hiking into vestal nature around Florida, the first with his wife, the second alone with the exception of the haunting reflections of Henry David Thoreau.

The second part of these two are especially interesting from a stylistic standpoint. While each section is headed with the aphorisms and extended metaphors of Thoreau from “Where I Lived, and What I Lived For,” the second person narration is pared down yet stream-of conscious in a similar manner found in Hemingway’s The Snows of Kilimanjaro, and found in VanderMeer’s latest novel Finch:

This section seems to last forever, and even as you remain vigilant, scanning the trail ahead for signs of motion, still your thoughts stray, time become elongated and porous. There’s the memory of each past experience traversing this stretch, and the awareness that you’ve come early enough to beat the biting flies for once, and then you’re somewhere else. You’re driving across Hungary toward Romania in a tiny car. You’re lost with your wife on a plateau in a park above San Diego, where the grass is the color of gold and reaches to your knees and the tress are blackened from fire….

You’re back in the first year of college when you wanted isolation and walked the five miles from the campus home in utter silence every day, receiving the world through a hole in your shoe and knowing you weren’t lonely but just alone. These thoughts are an embarrassment to you later. They seem to give significance to the mundane, but heightened awareness combined with a strange comfort is a signature of being solitary in solitary places.

While it seems the only monsters in this essay are the native animals—dolphins feasting unexpectedly at St. Mark’s, alligators, bears, herons, turtles—the piece is a nice conclusion to the monstrous theme by integrating the Romantic notions of sublimity. There is nothing more monstrous than the confrontation of Nature, an experience that is becoming more elusive everyday thanks to tourism, development, and the threat of man-made disasters. At the core of this sublimity, and what is at the core of most of this book, is that fantasy can be found in the most unlikely places, and is inevitably found in the last place you are looking: the real world.

S. J. Chambers is Senior Editor of Articles at Strange Horizons, and has had her non-fiction appear there as well as in Fantasy, Bookslut, Mungbeing, and The Baltimore Sun’s Read Street.